In the 1960s, when the electric car looked more like a far-fetched science fair experiment than a relatively convenient way of moving people and goods, investing in electrification made little sense. And yet, it’s the early, rudimentary prototypes that paved the road for the current crop of EVs. For example, BMW displayed a stunning amount of foresight when it built a pair of electric 1602s and tested them during a major sporting event.

BMW launched this ambitious project in 1969 and planned to have a running prototype ready in time for the 1972 Olympic Games, which were set to take place in its hometown of Munich, Germany. Developing an electric car from scratch was ruled out for cost reasons.

The brand’s range was much smaller in the 1960s than today, so picking the 1602 as a starting point was almost a no-brainer. It’s the predecessor to the modern-day 3 Series, and it was a popular model that played a sizable role in establishing BMW’s image as we know it today.

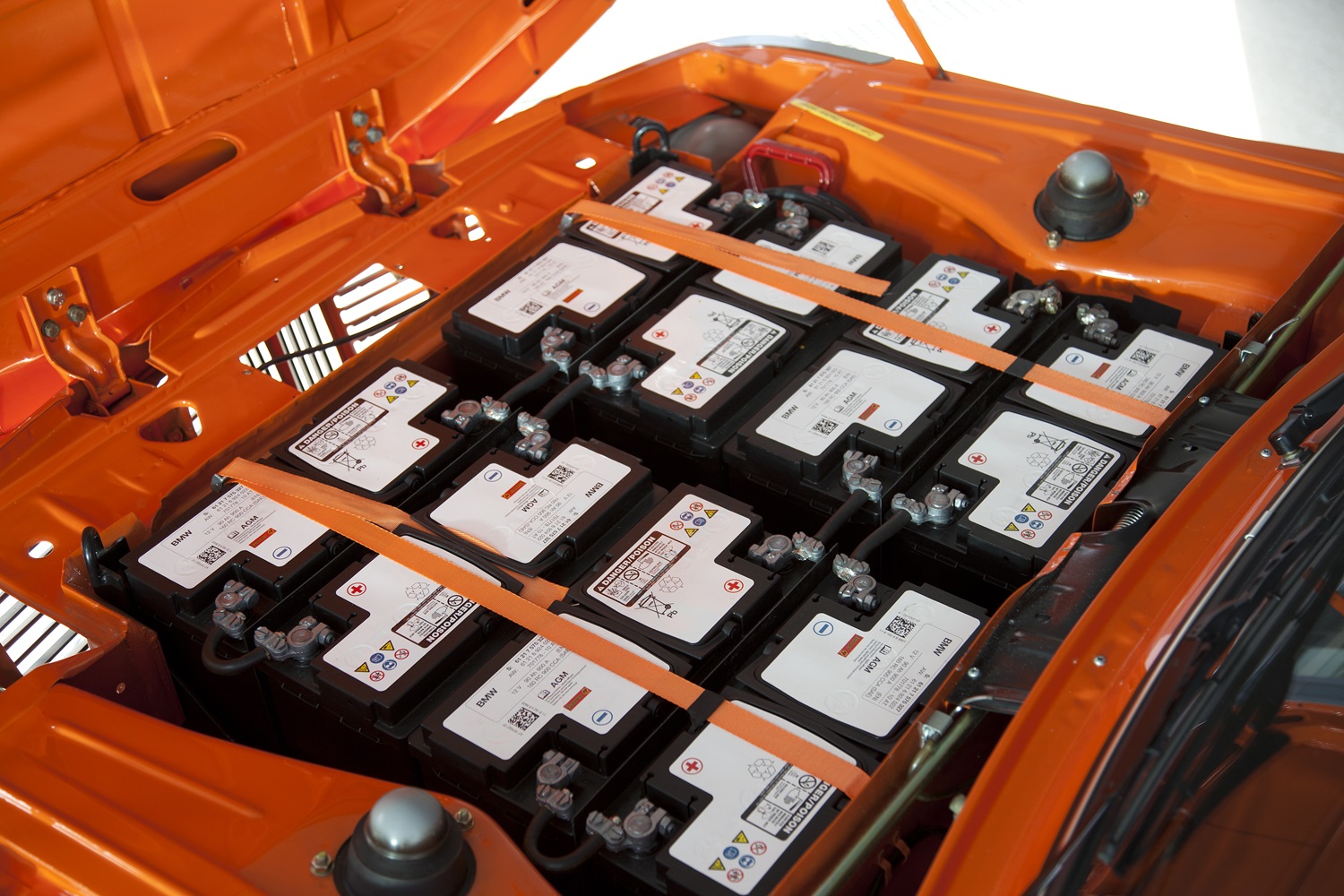

Power for the electric 1602 came from a DC shunt-wound electric motor provided by Bosch and mounted in the space normally occupied by the manual transmission. It was zapped into motion by 12 lead-acid batteries with a total capacity of 12.6-kilowatt-hours. BMW couldn’t buy an off-the-shelf battery pack from a supplier, so it did what it could: the batteries were standard 12-volt units mounted on a pallet. But as primitive as it might sound, the seeds of modern EVs had already been planted and the drivetrain featured a regenerative braking system.

The pack weighed about 770 pounds. For context, the standard 1602 tipped the scale at roughly 2,070 pounds. The added mass severely compromised performance: reaching 31 mph from a stop took eight seconds, and with enough tarmac, you could eventually get to a top speed of 62 mph. Lead-acid batteries aren’t as dense as today’s lithium-ion batteries, so range was dismal: 19 miles in city traffic and up to 40 miles when driving at 31 mph. The charging time was long enough that it made more sense to swap in a fully charged replacement than to wait.

These were less-than-glittering figures, but they represented the best that could be done with the technology available at the time. Converting a 1602 to electric power was nonetheless an achievement that BMW was proud of. The company built two prototypes, and members of the organizing committee used them to get around during the 1972 Munich Olympics. The EVs also served as camera cars for various events and as support vehicles for the marathon. Selling a regular production version of the car to the public was entirely out of the question due to the dauntingly experimental nature of the project, however. At least one prototype remains, and it’s sometimes displayed in the BMW museum.

BMW didn’t stop there. Leveraging the lessons learned during the 1602 project to make improvements, its engineers continued developing electric technology in the 1970s and the 1980s. Built in 1975, and largely kept secret, the follow-up to the 1602 was based on the LS and powered by a DC-series electric motor linked to 10 lead-acid batteries. Advancements included a charging system with an automatic shutoff mechanism. EV owners take this feature for granted in 2024, but it was considered a game-changing innovation nearly 50 years ago.

In hindsight, the 1602 prototype set BMW on the path to electrification. Electric technology has improved significantly over the past five decades. The 2025 i4 boasts up to 536 horsepower, up to 277 miles of driving range, and takes 3.7 seconds to reach 60 mph from a stop.