“Is that the robot?” says a voice at my back. “Is that the robot? Is that the robot? Is that the robot? Is that the robot? Is that the robot?”

Behind me, a Florida-orange senior citizen, in her orange blazer, wearing orange earrings, an orange bead necklace, and a white summer fedora, stands on the tip-toes of her orange leather loafers to get a better look at the weird scene unfolding in front of the crowd in the lobby of Lincoln Center’s Alice Tulley Hall in midtown Manhattan.

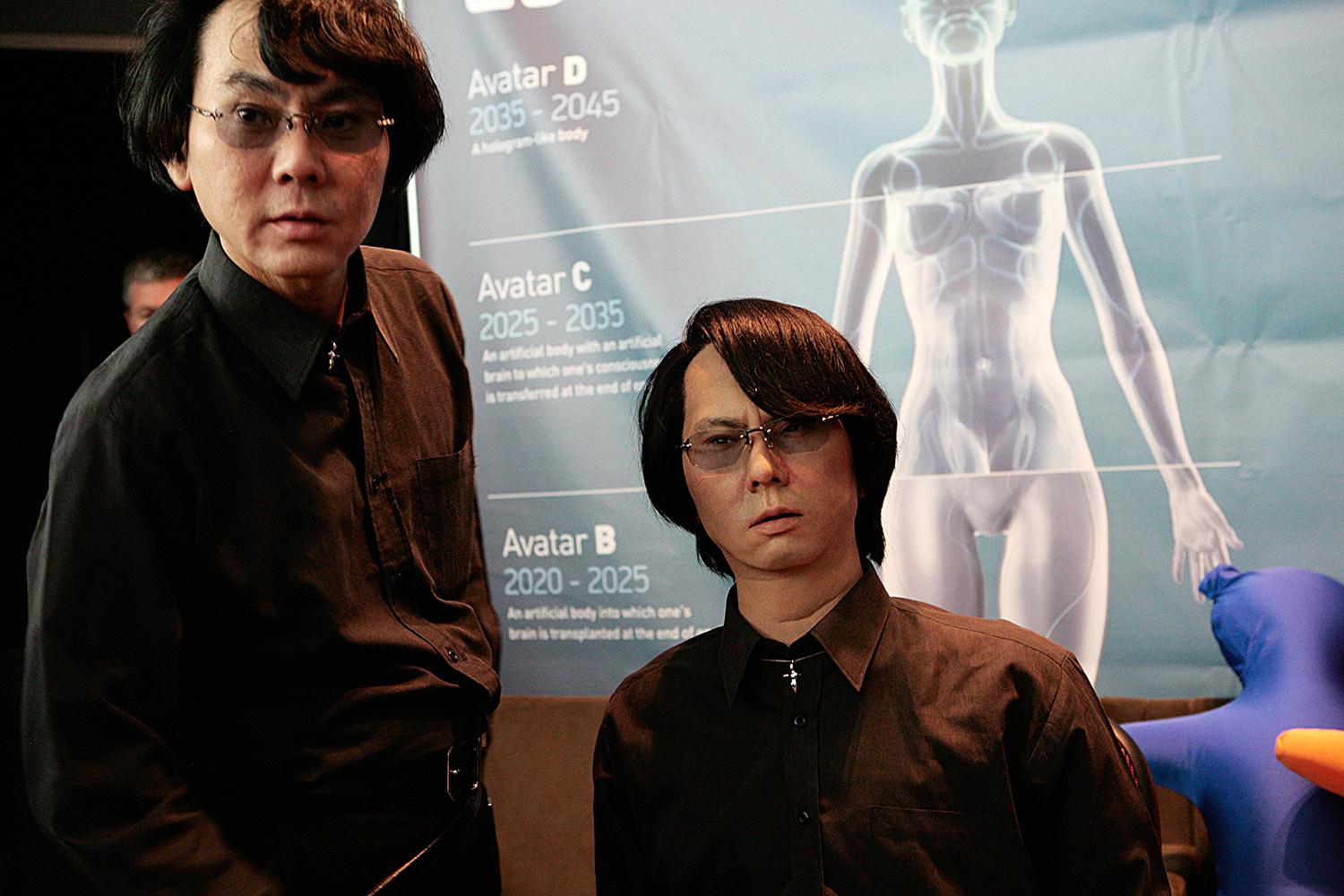

“Yes,” I tell Orange Woman. “The one sitting down is a robot. The one standing up is the guy who made him … er … it.”

“Oh!” she says. “I couldn’t tell the difference.”

“Gemanoid HI-2,” as it’s called, is an exact replica of its eccentric creator, Dr. Hiroshi Ishiguro. Same hair. Same all-black shirt and pants. Same little necklace. The only discernable difference between the two is that, while Dr. Ishiguro tells jokes, Mr. Gemanoid sits silently, slightly cross-eyed, blinking and jerking its head, with the eternally confused look of someone who suffered a paralyzing stroke while contemplating the ethics of Westboro Baptist Church.

In a tripod contraption next to Gemanoid hangs another of Ishiguro’s creations – a demented Casper the Ghost with all the charm of an aborted fetus. Its legs are a fused-together chunk. It has no hands, holes in place of ears, and the Mona Lisa smile of something undead. Ishiguro calls it Telenoid, an android designed with human-like features, but without all the pesky details that save onlookers from missing out on cold-sweat nightmares.

“Well, that’s just wonderful,” says Orange Woman. “It’s so lifelike!”

“If you think that’s impressive,” I say, “wait ‘till you see David Hanson’s android head. It’s supposed to be the most realistic android ever created. I hear it’s amazing.”

These are the conversations you have at the second annual Global Future 2045 International Congress, a lavish two-day event organized and self-funded by 32-year-old Russian Internet magnate Dmitry Itskov for the explicit purpose of promoting an “evolutionary strategy” of the human race – a strategy that, if its proponents are right, concludes with the lot of us uploading our consciousness into machines, to live for eternity.

The launch of the 2045 Initiative, of which GF2045 is but one piece, began after Itskov had a “spiritual transformation” several years ago, he says. And from this transformation, he emerged with the fundamental belief that the only way to save humankind from destroying our planet and ourselves is to change humanity itself – by fostering the science and technology that will let us become, you guessed it, immortal cyborgs.

His complex PowerPoint slides are entirely in Russian, “But you can guess what it says,” he says to the crowd. It’s unclear if he’s joking.

Soft-spoken, bashful, yet endlessly enthusiastic about his cause, Itskov gathered 30 elite speakers with a range of disciplines, from Harvard geneticist Dr. George Church to X-Prize Foundation founder Dr. Peter Diamandis to Google engineering director Ray Kurzweil, all of whom are, in one fashion or another, moving us toward the realization of Itskov’s dream that we become god-like machine-people by the year 2045.

It’s audacious – some have called it crazy – but to hear these pedigreed brainiacs tell it, the plan might just work.

The conference kicks off at 9am on Saturday morning with a heavy dose of fear mongering by Dr. James Martin, the stereotype of a British intellectual, who emcee Philippe van Nedervelde introduces as “the greatest living patron of the sciences,” and “Oxford University’s largest benefactor in 900 years.”

A tenacious pessimist, Martin takes the GF2045 crowd through a series of “paradigm shifts,” from the beginning of human suffering, through wars and poverty, through famine and global climate change, to a future in which we all burn alive in a desert of our own greedy creation.

“This century, the 21st century, is a make-or-break century,” says Martin. “There are some very dangerous things happening. And if we don’t get it right – if we don’t control climate change before it becomes a runaway tipping point, if we don’t do that, then it’s going to be very dangerous for many of us.”

Martin goes on like this for nearly an hour, providing overwhelming proof that “a crunch is coming” – that we do, in other words, need to become cyborgs. By the end of his talk, I’m frightened and exhausted and it’s far too early to start drinking.

Mercifully, Martin’s recipe of ruination is quickly washed away by the next speaker, “Big History forecaster” and Russian Academy of Sciences Senior Research Fellow Akop Nazaretyan.

Big History explores the scientific transformation of nature and society through a range of disciplines, from biology to the humanities. Nazaretyan’s theory is that human intellectual activity is so powerful, it can change the physical shape of our universe – at least, that’s what I think he is talking about. His complex PowerPoint slides are entirely in Russian, “But you can guess what it says,” he says to the crowd. It’s unclear if he’s joking.

The first three-hour block of speakers caps off with a barnburner by technology entrepreneur, best-selling author, and Singularity University co-founder Dr. Peter Diamandis. He woos us with the expert salesmanship of a motivational speaker into believing that, despite what supreme downer Dr. Martin says, things are looking up for ol’ humankind.

“We as humans are far better at seeing the negative, dystopian futures than the positive ones,” says Diamandis. “We see the dangers far, far away. But ultimately, we do have the power to solve them in advance. And we do, over and over again.”

Transhumanism isn’t on his “immediate focus horizon.” And that’s coming from a man whose current business endeavors include mining asteroids in space.

There is a reason this man has more money than God. By the end of his speech, I feel downright chipper.

Despite Diamandis’ unwavering assertion that future technologies will set us free from the shackles of doom, he doesn’t once mention Itskov’s goal of cyborg immortality – the whole reason we find ourselves at GF2045. The omission seems odd, almost suspect. So, I catch up with him in the lobby to ask how his vision fits in with Itskov’s.

“It’s all a blur of the same thing,” he says with a yada-yada tone. “The end result of abundance is enabling people to have a better life, with less struggle, and to fulfill their objectives, and having to – you know, literacy, health, clean water, food, and so forth.”

Diamandis, who appears a little annoyed that he allowed himself to be cornered by a relative peon, says that, while “transhumanism – as in uploading your brain” is “eventual,” it’s not on his “immediate focus horizon.” And that’s coming from a man whose current business endeavors include mining asteroids in space.

After a quick coffee break, the next few hours before lunch lumber by, with talks from our quirky roboticist, Ishiguro; and UC Berkley scientists Dr. Jose Carmena and Dr. Michel Maharbiz, who have developed ultrasound-powered “neural dust” for next-generation brain-control prosthetic devices – an advancement so wild it almost makes you wish for a traumatic brain injury.

During a roundtable discussion, neuroscience pioneers Dr. Mikhail Lebedev and Dr. Theodor Berger discuss the ins and outs “manipulating memories” into 1s and 0s, and the future ability to transplant human brains into other vessels. Just when things start to get weird, Itskov appears on stage to make his big pitch.

There are people “literally dying right now” who could be saved by brain transplant technology, he says. Which is why he’s launching a lab in the U.S. to develop this kind of life-saving “humanitarian” technology – the kind of technology that businessmen should get in on while it’s still young.

“It would be a huge breakthrough,” says Itskov. “The partnership could be different. Businessmen could probably give their name to the project, to save the history, and to have their own avatar once the [science has evolved].”

As if to sell his transhumanist future even harder, out comes real-life cyborg Nigel Ackland, a former precious metals smelter from England, who was fitted with a Bebionic3 artificial hand – the most advanced prosthetic on the market – after half his right arm was crushed in an industrial blender. For Itskov, he’s a masterstroke of marketing genius.

Ackland’s new hand and forearm contain sensors that detect muscle movement in his upper arm, which translate into movements of the Terminator-like fingers. Depressed and overweight, Ackland once felt like his life was over. The hand, he says, has made him human again.

“… People would tend not to come and talk to me, they would tend to keep away from me, they would tend to move me almost to the edges of society,” says Ackland. “Now, everyone just walking around today has wanted to shake my hand.”

You can almost see the tear ducts and wallets in the audience open up.

Our elation is soon tampered by a strange announcement: Roboticist David Hanson, who is scheduled to debut “the world’s most advanced android” – a robotic head designed to look identical to Itskov, packed with a remote controlled “telepresence” interface – after the lunch break is still “tinkering” on the device at his home, and will not present until the next day.

Tinkering? I recall a conversation I had with Hanson in March, more than two months earlier. “The time schedule is fantastically short for this particular project,” he told me. “I mean, we basically received this commission about a little less than two months ago. So we’re talking about a very, very short time frame for making a redesign of the human-scale technology to improve it, customizing it to be Dmitry, and then bringing together the best of our technologies available to achieve a remote control version of Dmitry.”

But he’s coming, I think. He has to. Not only is Hanson’s creation one of the primary reasons I’m here, it’s the one concrete proof Itskov has to show that his ideas aren’t just grand theories and big talk. Tomorrow, I tell myself. Tomorrow.

The next morning, the King Transhumanist himself, Ray Kurzweil, schools us on all forms of science and technology: Mobile phones, quantum physics, Moore’s Law, health care, 3D printing, brain mechanics, the full gamut. Despite all his wisdom and knowledge, however, the most notable thing he says – besides disputing the prominent theory that the brain is a quantum computer – is that rich early adopters, like those who bought the first cell phones, are idiots.

“Twenty years ago, only the rich had [cell phones]. They didn’t take it out of their pockets – it was a brick!” Kurzweil explains. “It didn’t work very well, but that was a signal that this person was a member of the power-elite. Only the rich have these technologies when they don’t work.”

By the end of his talk, I’m frightened and exhausted and it’s far too early to start drinking.

The crowd – most of whom are male, many of whom appear to be rather similar to the fools Kurzweil talks about – gives this a hearty round of applause.

Save for a fascinating talk by Dr. Berger about his ability to recreate rat memories on transplantable microchips, and Dr. Church’s explorations into the human genome, the rest of the talks drone on with the kind of scientific complexities that only a PhD student can love. Quantum consciousness, mapping the brain’s connectome, whole brain emulation, reverse engineering the brain. It’s all riveting, but I struggle to stay awake, exhausted by the sheer intricacy of this future that they insist is inevitable. And besides, I’m just waiting around for 2pm, when a GF2045 PR woman told me Hanson and his nifty Itskov-borg are supposed arrive on stage.

By 3pm, I begin to worry. I run to the front desk, and interrupt the PR woman.

“Any idea on when Hanson is getting here?” I ask.

“Well, his plane just landed at La Guardia,” she says. “But I don’t have confirmation on that. It depends on traffic, but maybe 4:30?”

Back in the auditorium, the conference begins to devolve into a shitshow, as the religious portion of the event picks up steam. Dr. Amit Goswami delves into the “consciousness and the quantum.” Swami Vishnudevananda Giri gets too new-agey for comfort, with talk of the relationship between “Vedic culture and cybernetic technologies.”

People begin to pull out their laptops and tablets. The group next to me laughs openly at the speakers on stage. The clock, of course, keeps ticking – 4:00, 4:30, 5:00. By the time the religious roundtable begins at 5:30, I know my dreams of seeing the most advanced android on the planet will not come true. Hanson has missed the ship to the future.

As soon as Dmitry finishes his closing remarks, I bolt to the lobby to find the PR woman packing away her computer, a perturbed scowl on her face.

“So, did Hanson not get here?”

“He’s backstage.”

“Backstage! What happened?”

“Apparently, Dmitry isn’t very happy with it. It doesn’t work quite well enough to show on stage. I guess it doesn’t even look like him,” she says, defeated. “Dmitry made the decision. I’m sure he’s very upset.”

I rush back to the auditorium to try to catch Itskov before he goes into hiding. But as I reach the doors, the event workers usher us all out into the lobby. The doors to the auditorium close. And I’m left outside, circling the building, trying to find Itskov, trying to understand what just happened. But he’s nowhere to be found.

Two days later, an email arrives in my inbox entitled “Android Head Statement.” A statement from the android head? Alas, it is just a comment from Itskov further hanging Hanson’s android head in shame.

“We so appreciate the patience and support of everyone waiting for what we thought might be a concluding crescendo to the congress,” writes Itskov. “But just like many other technological advances, failure is sometimes a part of the road to success. While we had hoped to see the android head in full working order weeks ago, there were delays and it arrived in a much too premature condition to show to the public. We hope that we can show you something very soon.”

Part of me roots for Itskov, a good man with laser focus and a strange hobby. I believe, as he does, that we humans will continue to free ourselves, inch by inch, from the prison of our imperfect biology through science and technology. But the bars between us now and an immortal cyborg future are thick and resolute. And in the mean time, as we pick at the locks, I’ll be scrounging up my shekels – there’s an asteroid mining company that seems like a safer investment.