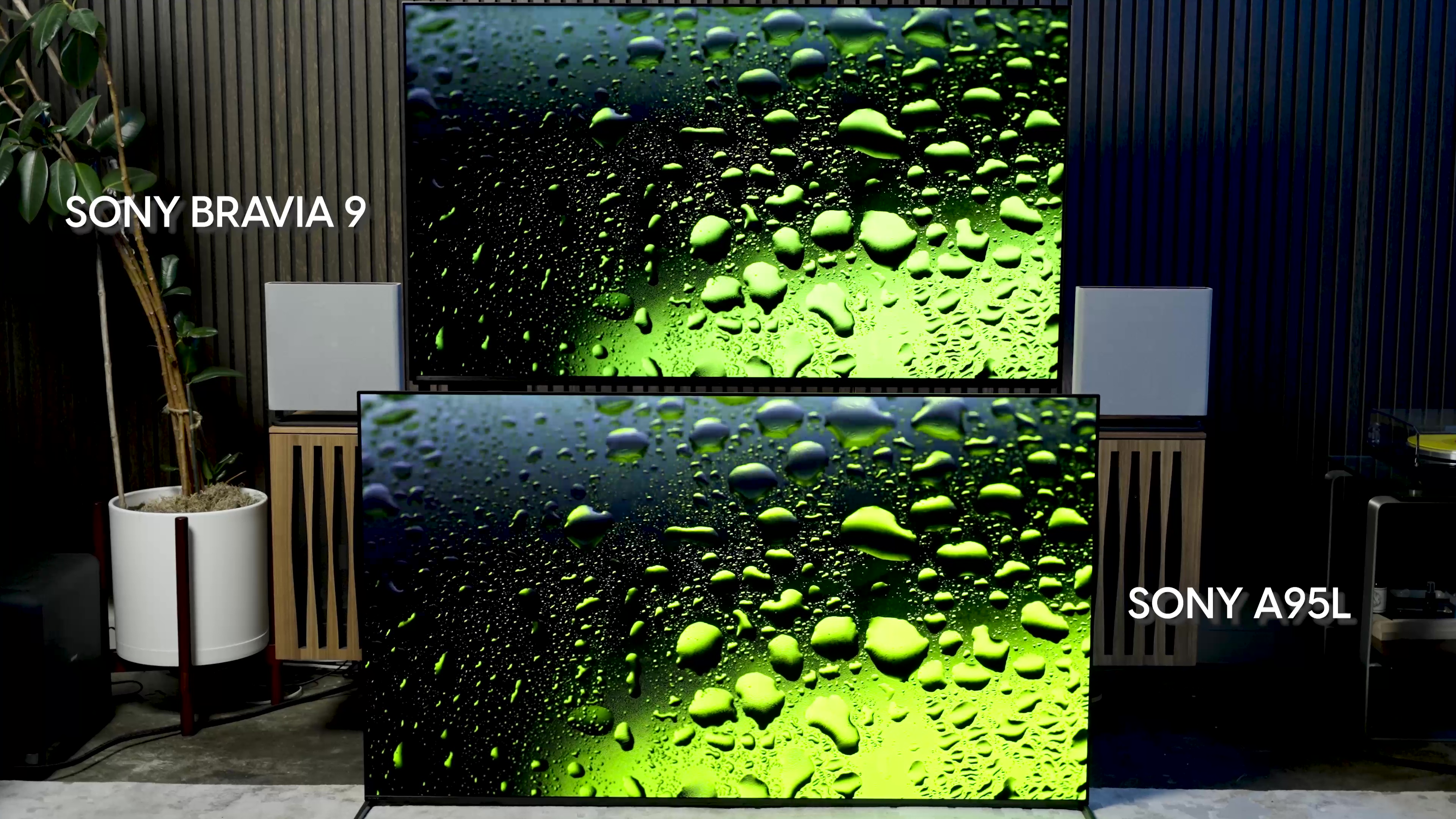

This is one of those times when we get to pit two of the best TVs available against each other. We have the Sony Bravia 9 — the most advanced mini-LED QLED TV made to date — and the Sony A95L, regarded by many (myself included) as the best OLED TV made to date.

This is mini-LED vs. OLED. This is the best QLED versus the best OLED. They are, to be clear, very different technologies. Mini-LED/LCD will never match OLED in a few key areas, and OLED will never match mini-LED/LCD in a few key areas. In other words, if you want to know what’s going on with the state-of-the-art in TVs today, if you want to know why there is no single “best” TV, why there isn’t and probably never will be a “perfect” TV this will help explain things.

TV screens essentially are big technological sandwiches. An LCD TV screen is a triple-decker club sandwich. There are a lot of layers, but man, do they pack a powerfully tasty punch. OLED TVs are like tea sandwiches — thin and simple in their build, but delightfully exquisite — so tasty you just want to eat more and more and more of them.

The LCD TV has a lot of layers. There’s a diffuser, a polarizer, a color filter, and lately a quantum-dot layer. There are a bunch more, too, but the layer I want to hone in on right now is the backlight layer. Behind all of this stuff is basically a bunch of LED light strips.

The Bravia 9 is a mini-LED TV, which means there are lots of tiny lights. The light emitted by those glorified light strips goes through a diffuser layer so the light gets spread out. It then goes through a polarizer that controls light waves, and then the light goes through a color filter. And then, finally, that now-colored light is either allowed through or mostly blocked out by the LCD — or liquid crystal — layer. The light starts at the back, travels through a bunch of processes, and then flies out into the room, aimed at your eyes. We call this transmissive — because the light is transmitted from an origin, through a process, then out to our eyes.

OLED TVs have very few layers, which is why they are so thin. And the reason they have so few layers is because there is no backlight, no diffuser, no polarizer (at least not down deep), and no color filter. Instead, there are little cells filled with organic material that light up when you hit them with electricity. Each individual, tiny pixel makes light. That’s why we call these emissive displays.

That technical difference — that one TV uses a backlight and an LCD layer, and that the other has pixels that make their own light — makes all the difference in the world.

Why the difference

The human eye perceives the difference between dark and bright more readily than any other visual element. That contrast, even more than color, is where a TV really needs to excel in order for us to look at it and say “wow.”

Because each pixel in an OLED TV emits light — or not — they are extremely good at contrast. Colors are brighter, and blacks are totally black. And when you start from pure black, you set the stage for infinite contrast. It’s just a question of how bright you can get on the other side of the spectrum.

The problem with LCD technology is that the liquid crystals are not very effective at blocking out light.

First I need to explain why LCD TVs — even one as good as the Bravia 9 — have to pull off a whirlwind of tricks in order to achieve what OLED does naturally.

The problem with LCD technology is that the liquid crystals are not very effective at blocking out light. When this liquid crystal window shade is closed, it blocks most of the light. Some light still manages to seep through. This is why the first LCD TVs had really bad black levels. The backlights were always on, so the only way to get something dark out of the TV was to rely on the liquid crystals to block the light. And they just aren’t good at that.

So TV manufacturers had to get clever. If the LCD cell isn’t good at blocking light, then the best way to get closer to black is by not having any light behind the LCD cell in the first place. And, thus, local dimming was born. The TV shuts off the LEDs behind the LCD, and the TV gets better blacks.

This approach created a new set of problems, called blooming and halo. While the lights behind this dark area of the image can be turned off and provide a really good sense of black, the lights behind this bright object still need to be on. And because we know that LCD cells can’t block out all of the light, that means that the closer you get to the bright object, the more you’re going to see light bleeding through.

The solution to that challenge was to use more LEDs and break them down into more and more zones that could be dimmed, getting ever closer to having more precise backlighting, and mitigating some of that halo and blooming.

On a macro level, the difference between this big bright object and this big black area is extremely high-contrast.

But there was still an opportunity to make this backlighting even more precise. That’s where mini-LEDs come in. By using much smaller LED lights, the TVs have even more precise control of the backlight, illuminating much smaller areas of the screen. And break down the massive number of mini-LEDs into an equally massive number of zones that could be dimmed, there’s now an even more precise backlight. That’s when the halo and blooming gets so minute that it’s really tough to see it at all.

Sony then took it a step further and made the mini-LEDs so they weren’t just binary — on or off — but added, like, 12 different stages of brightness. So there’s now even more precise control of the backlight and the least amount of blooming and halo we’ve ever seen from a mini-LED backlit TV.

So you might think, then, that with such incredibly precise backlighting, and virtually no halo or blooming to be seen any longer, that this mini-LED would have contrast on par with an OLED TV. In fact, folks were so hopeful for that that the term “OLED killer” started getting tossed around. And yet when we compare this mini-LED TV to this OLED TV, it is readily apparent that the OLED has better contrast.

But how can that be? This part of the screen is as black as it can get, right? And there’s no glow around this bright object on this black background, right? Well, yes, that is true. On a macro level, the difference between this big bright object and this big black area is extremely high contrast.

But the lingering difference — the reason this OLED looks more contrasty than this mini-LED LCD TV — is hiding at the micro level. Which means to show you, we need to use a microscope and really zoom in on what’s going on.

The contrast is hiding in areas like this. Here we see a a group of trees. We can see some leaves, but the space between the leaves is dark. On the OLED TV we can see that some pixels are extremely dim, if not turned off entirely. But, if we move to the LCD TV, we can see in the same space that the dark areas next to the bright areas, at the pixel level, have much lower contrast.

The only way to make one pixel bright and the pixel right next to it totally dark is if you can control each individual pixel.

And that is because there’s no way to stop light from bleeding through the LCD cells that are turned off. The only way to make one pixel bright and the pixel right next to it totally dark is if you can control each individual pixel.

So what happens is the contrast in these tiny areas on this mini-LED TV simply cannot be as good as the contrast in those same areas on an OLED.

Big picture, little picture

When we zoom back out, it almost seems silly to think about our eyes honing in on this one tiny section of the image. And that’s fair, because our eyes don’t do that. But if you think about the micro-level contrast at the macro level — the fact that there is better pixel to pixel contrast in hundreds of thousands if not millions of areas all across the screen? You begin to realize that the aggregate of all those little micro contrast points add up to something that our eyes can perceive.

And that, folks, is why OLED will always beat LCD at contrast. LCD technology will never overcome this limitation. It is not physically possible. Not unless there’s a way to control the light behind every single pixel on an LCD screen.

If you are a display geek, then you already know there is a way — called dual-cell. (You’ve read about it in our Hisense U9DG review.) But dual-cell is expensive to make well, and doesn’t work great at the consumer level. Dual-cell tech tends to dim down an LCD TV so much that the trade-off isn’t worth it. Today, we only see dual-cell used in super-expensive professional displays.

So if OLED is the undisputed king of contrast, then why aren’t all TVs OLED TVs? There are two primary reasons. One is that OLED TVs are more expensive to make, and thus they are expensive to buy. But the other reason is just as important: OLED TVs struggle to get as bright as LCD TVs. And while true blacks deliver a higher-impact display of contrast, there is something to be said for brightness, too.

Today’s most advanced OLED TVs — also the most expensive OLED TVs — can now provide just as much brightness punch in small areas as LCD TVs. Here’s an example of that — the 4,000 nit flames in this scene are just as bright on this A95L OLED as they are on the Bravia 9 mini-LED.

But for brightness across the entire screen? That’s where OLED TVs still struggle.

And when you are watching in a room with a lot of bright ambient light? You’ll need the TV to get pretty bright in order to feel like you are getting great contrast. That’s where full-screen brightness power comes in handy, and that’s why LCD TVs are still preferred in these situations. Because while it is true that an OLED TV like the LG G4 can get plenty bright, even for a bright room, it costs so much more money compared to a comparably bright LCD TV. That it just doesn’t make sense for most people.

Micro-LED is the best of both worlds in terms of brightness, pure blacks, contrast, and color.

There’s one other thing to consider here. Let’s say, just for the sake of argument, that an OLED TV could get as bright at full-screen level as a mini-LED TV. And let’s say that manufacturing breakthroughs made OLED TVs less expensive so that they were just as affordable as LCD TVs. Would OLED TVs just eliminate the need for LCD TVs entirely?

No. Because OLED TVs have one more weakness. The O in OLED stands for organic. And what we know about organic things is that they have a shorter half-life than non-organic things. They break down. And what that breakdown looks like in an OLED TV is burn-in.

While burn-in has been mitigated over the past few years, it is still a risk, depending on viewing habits. And so long as that is the case, OLED can never eliminate the need for LCD-based TVs.

Micro-LED is the best of both worlds in terms of brightness, pure blacks, contrast, and color. But the problem with micro-LED is that it is hard to make the pixels tiny enough so that they can fit in a normal sized TV. I mean, it’s been done, but apparently the manufacturing process is expensive. So micro-LED, for now, is not going to kill either OLED or LCD.

Wide-angle club

One other thing I have to bring up is wide-angle viewing. This is another area where the gap between OLED and LCD has been narrowed. There are now some LCD TVs that have great off-angle. And some OLEDs might show a slight tint when viewed at extreme angles. Still, even the least-expensive OLED TV is going to offer a better picture when viewed off to the side than an LCD-based TV of equivalent price.

There are trade-offs to be made with either technology — even the best examples of each technology. There are limitations for each that will never, ever go away. That means we have to turn our attention to other picture quality elements, sure, but there’s so much more to a TV than picture.

The Bravia 9 here has a killer audio system that in some ways outpaces the very good audio system on the A95L. It’s got a rechargeable remote, which the A95L doesn’t have. Those may seem like small things, but when the picture quality isn’t swaying you one way or another, those little things may make the difference.

Hopefully you now understand why no perfect display exists. No perfect TV exists. Are we close? Absolutely. But we’re not there yet.

There is no such thing as a best TV for everyone.

So for now the challenge is to figure out what kind of TV is right for you. There are several considerations to make, and everyone’s needs are different.

Because there is no such thing as a best TV for everyone.

There’s more to TV picture quality than just contrast. There’s the matter of color accuracy, high brightness color saturation, upscaling and motion processing and such. But not everyone can tell the difference between one TV and another when considering those elements of picture quality. Contrast, though? That’s something that resonates with everyone.