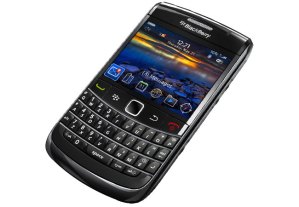

A report in the Indian Daily The Economic Times claims that Indian security agencies now have manual access to messages sent on RIM’s BlackBerry Messenger service, and expect to have fully automated access to the messaging service by the end of the year. According to the report, security agencies are receiving decrypted copies of BlackBerry Messenger communications within four to five hours of placing their requests with RIM; once automated services are in place, Indian security officials should be able to monitor chat communications in real time.

India had originally planned to block BlackBerry Messenger at the end of August, citing security concerns that militants and terrorists could use the services’ encrypted communications capabilities to plan and coordinate attacks. RIM won a 60-day reprieve while the company worked with Indian officials to see if a workaround could be reached by locating BlackBerry servers in India, rather than at overseas data centers. That 60-day extension is due to expire October 11.

According to The Economic Times, access so far is limited to BlackBerry messenger; so far, RIM has apparently not come up with a mechanism to access unencrypted copies of messages sent via corporate email services.

Claims that RIM is able to deliver unencrypted copies of BlackBerry Messenger exchanges—and that the process can apparently be automated to take place in real time—flies in the face of RIM’s repeated claims that it doesn’t have any backdoor to encrypted communications on its services. RIM has maintained it deals only with encrypted data, and that only BlackBerry users have the keys necessary to decrypt the messages, since they generate the keys themselves. RIM has also claimed it doesn’t give preferential access to any single government.

India’s government also says it plans to go after other forms of encrypted online communications, including services like Skype and Google, and mandate that security agencies have access to communications on the services. Nokia has already said it will comply with India’s requirements for access to communications.

Of course, enabling government agencies to tap into communications opens a minefield of issues: backdoors could be abused by third parties or individuals within the government, even if access is supposed to be restricted to lawful purposes. Governments could also use the backdoors as a way to monitor communications for content they deem politically or morally objectionable.