“It resonated the way I felt at the time,” Dave Davies says of his signature guitar riff on The Kinks’ seminal power-chord pop masterpiece “You Really Got Me,” which, in an instant in 1964, forged how artists could harness distortion on studio recordings. And it started with mutilating equipment.

Davies literally set the template for the mood, tone, and sound of heavy metal, hard rock, and punk in one fell swoop when he used a razor blade to slice up the speaker cone inside the Elpico amplifier that was slaved into the Vox AC-30 he was playing through at IBC Studios in London on that fateful July day a half-century ago. “I wanted something that I felt would help with the interpretation of my anger and my emotions, and that’s what did it,” he explains.

“Those little mistakes you make are actually good and quirky and interesting.”

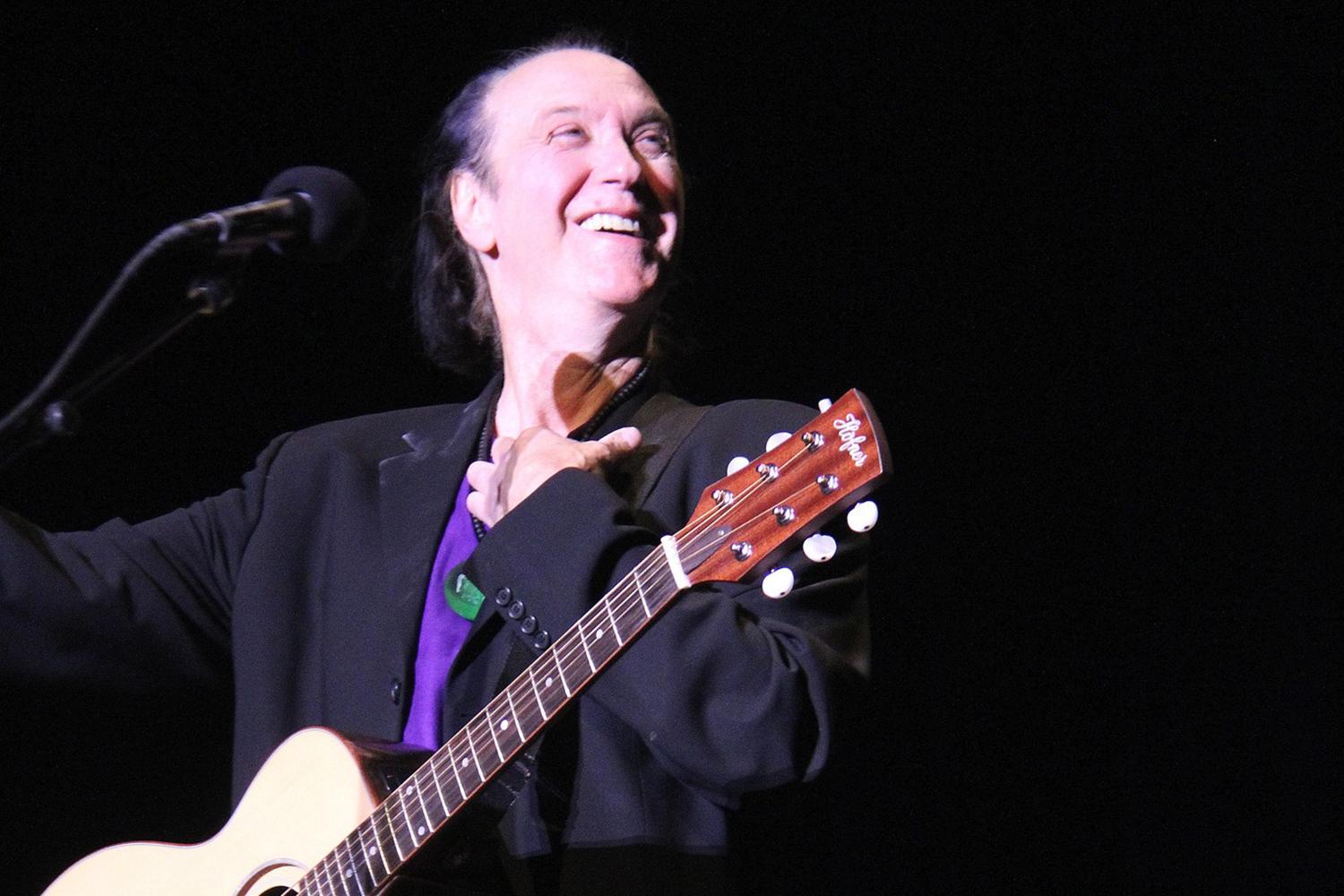

While The Kinks are currently shoring up plans for how to properly celebrate the band’s 50th anniversary, Davies continues to cut new sonic swaths with his just-released seventh solo studio album, Rippin’ Up Time (Red River). Thanks to the seductive horn lines and percussion buttressing the lip-service sendup of “King of Karaoke,” the headbanger-balling riffage propelling the hip-hopping verses on “Mindwash,” and the raucous trade-off of father and son taking the collective piss out of “In the Old Days,” Davies proves he still knows how to do it all of the day and all of the night.

Davies, 67, called Digital Trends from his home in New Jersey to discuss his views of high-resolution audio and surround sound, communicating emotion through music, and the benefits of working with family members. “No, I don’t have a Jersey accent,” he laughs. “I don’t think it suits me.” Dave, you really got us.

Digital Trends: You’ve seen and heard a lot of music-playback formats over the years. What do you think about high-resolution audio?

Dave Davies: High resolution is something that’s really quite powerful. There’s something about older music that works in that form because it sounds, sonically, of its time — and high resolution enhances it rather than changes it.

To me, the key word you said there is “enhances.” If hi-res audio lets me hear more detail or clarity in someone’s playing or elements that got buried in older or inferior mixes, I’m all for it.

Oh yeah, of course. It allows for the more pristine elements in the music to come out. When I was making Rippin’ Up Time, I was mostly concerned about getting the feeling, the emotion, and the ideas across. That’s always a priority for me — getting the emotion across exactly how I want it.

Where did you record the album?

Most of it was recorded in my friend David Nolte’s studio in Los Angeles. He’s got a really cool studio in his house. We’ve worked together for a long time, going back to the ’90s, and we became good friends. We work quite quickly together. It took us about six weeks to get the ideas out. I went to L.A. on July 1 and came back to Jersey on August 20.

“There’s a lot that goes into doing the “simple” sequencing on a record.”

Did you expect it to go that quickly?

No, I didn’t, actually. But sometimes that happens when you get ideas that gel really quickly. It came out like that. And that’s how I like to record anyway.

I particularly like the beginning of “Semblance of Sanity” — the way how you say “shhhhh” ping-pongs between the left and right channel and the overall echo on your vocal.

Thanks! I also really like the keyboard parts on that song. There’s a really rhythmic thing I was going for there, that ambience. It really set the tone for that song. But I like them all for different reasons.

It’s one of my favorites. I also love the historical context of “Front Room” and how you sneak in that certain signature riff from “You Really Got Me” near the end of it. Do you get double royalties for doing something like that?

(laughs) It should be that way, really.

Considering how just about everybody else has borrowed it —

Yeah, from A to Z, I think. (chuckles) That song — that riff has inspired a lot of musicians and writers over the years. It’s very dynamic. The thing about “Front Room” is I wanted to write something about the time that The Kinks were just a three-piece — me, Pete [Quaife, bass], and Ray [Davies, guitar/vocals] — and how we messed around in the front room. And, of course, that’s where the “You Really Got Me” sound came from, that front room. So yeah, it’s nice to look back and echo some of my concerns about the present and the future as well.

And you three guys all plugged into the same amp when you were playing together in that front room, right?

Yeah, it was a little green Elpico triangle-shaped amp, and we all played through it — a bass, and two guitars.

Amazing. Well, you had to make do with what you had.

It was the same when we started recording. We just made do with the instruments that we had.

“A lot of feelings and emotions that song conveys are just as important now as they were when we recorded it.”

You must have had a specific sound in your head you wanted to get — as in, “This is how I want to sound, and this is how I have to get there.” Were you able to describe what you wanted to hear? Was it based on something you’d heard before, or was it something you knew you could make yourself?

I don’t know, really. I’ve always been the sort of person who gets inspired through my feelings. If I like something that makes me feel a certain way, I’ll use it.

A number of guitar players, like Eric Clapton, have said that they speak better to people through what they do with their fingers on a guitar rather than verbally. Is that what you’re saying in terms of having your emotion come through in what you play?

Well, yeah. I also think emotions get in the way of what you want to say sometimes. (chuckles) And it’s easier to get the point across in music rather than lyrics. But you do need your imagination and a certain amount of lyrical prowess. Good music is a mixture of a lot of things.

Channeling the character of distortion like you did on “You Really Got Me” was a great innovation. Did you know you wanted that type of sound when you were jerry-rigging that amp?

I wanted something that I felt would help with the interpretation of my anger and my emotions, and that’s what did it — when I made that little green amp sound like it did by using the razor blade on the cone of the speaker. It resonated the way that I felt at the time.

Was there something that compelled you to pick up the razor blade itself, or just a curiosity about what it would do to the speaker?

It just occurred to me. I don’t know why. I just thought, “Oh, I’ll try it and see what happens.” And I was surprised it even worked. I didn’t expect it to, really.

That could be the most famous razor blade in the history of music. Do you still have it?

(laughs) No, I should have kept it! And I also wonder whatever happened to that amp.

I think we all do! And it’s become such a signature tone that we know it’s immediately you whenever those first notes ring out. That’s certainly the case when you cue up the title track to Rippin’ Up Time.

Well, thank you, yeah! That song came about in kind of a dreamlike way. I was thinking about that part and what I was going through in the past, seeing my life in the present, where I might be going, and what sort of future is going to be there for us.

At the beginning of the song, we hear your fingers moving on the frets and the strings. You captured the character of the chord changes rather than cleaning it up.

I wanted to keep it quiet and fresh without worrying about it too much. Sometimes you play things and they sound OK on the surface. And sometimes the first ideas you get can be the best — they feel edgy. I like the ideas you get first, so I tried to keep a lot of the feeling of spontaneity in there. When you sit down to start writing something, you may have no idea what you’re going to do. Those little mistakes you make are actually good and quirky and interesting.

We can certainly feel the emotion in your playing there, and you speak some of the vocals rather than sing them. That had to be a conscious choice.

Yeah, it’s like poetry. It gives the song a totally different effect. It’s a strange, mysterious effect when you talk through a lyric.

“High resolution enhances it rather than changes it.”

It’s also more intimate — more like you’re having a conversation with us.

That’s true too as well. I thought I’d mix the ideas up a bit there.

I want to get your opinion about the remastering of The Kinks catalog on SACD in 88.2kHz/24-bit PCM that started back in 1998. Some of those albums got a surround sound mix too. Do you like the idea of your music being in surround sound?

Yes. I think it’s all right. I tend to want to hear things in their optimal format. It’s nice to experiment with new ideas using that material. It has its pros and cons, but I like listening to the older songs when they have a different kind of sonic value to them.

I like it if it gives me a sense of being there with the musicians —

Like you’re literally in the room there with us, yeah. It makes you feel more intuitively connected with the music in some ways.

Yes, and that also ties into what you said earlier about getting emotion across with your material — which makes me immediately think of the feel of Muswell Hillbillies (1971).

Oh yeah, because it’s all about the characters and the stories, and the musical influences. I mean, we grew up on country & western music, the blues, and English folk songs, and elements of all of them are on there. It’s a very special album.

I’m partial to “Oklahoma U.S.A.” and “20th Century Man.” Do you have a favorite track on that record?

Oh, loads of tracks, but I think “Complicated Life” especially — you can relate a lot of that in today’s world. A lot of feelings and emotions that song conveys are just as important now as they were when we recorded it — people feeling fairly displaced, and how we all deal with morals.

Right. But I think you may need to rename the first track on there “21st Century Man.” It’s still just as poignant in a lot of ways.

Yes, it’s true. “Uncle’s Son,” the “Muswell Hillbilly” song itself — yeah, I love all of that album.

Getting back to Rippin’ Up Time, it’s nice and concise at 40 minutes. I felt the record took me on a journey with an earned payoff near the end of it with “In the Old Days,” the next-to-last song.

I like that; that’s great to hear. That’s what I had hoped. David [Nolte] and I spent quite a lot of time on the sequencing because of the pace and the emotion, and wanting to make it interesting to the listener. There’s a lot that goes into doing the “simple” sequencing on a record.

You had your son, Russ Davies, on “In the Old Days,” and also on the last track, “Through My Window.” Working with family has sure worked out for you in a lot of ways over your career, and this just makes it come full circle.

That’s right, and he co-wrote it as well. He sings the first verse. It’s very exciting to work with him. I had a great time. He has very definite ideas of what he wants to do.

I guess those traits come by way of his DNA, don’t they?

(laughs) Yeah! Oh, that’s great! (chuckles) In my group, I of course worked with [my brother] Ray, and now I love working with my kids. I think my son’s ideas helped make the album a bit fresher by the time it gets to the end. It covers my past, and how I feel now in terms of the future. I’m very proud of it.