“This record is the closest to the way we feel about the music that’s inside us.”

If you feel like the world keeps closing in on you, and you absolutely have to get away from it all, might we suggest you take a mind-cleansing ride with The Orb? The ambient-house pioneers — consisting of legendary DJ duo Alex Paterson and Thomas Fehlmann — are at it again on Moonbuilding 2703 AD, out today from Kompakt on various formats. Comprised of just four songs averaging 10 minutes apiece, Moonbuilding is drenched in modern electronic psychedelic magic, from the surface-noise swirls of God’s Mirrorball, to the ambient beat-driven wash of Moon Scapes 2703 BC, the ethereal and synth-dripping Lunar Caves, and the jazz-infused bass swoops that infuse the title track.

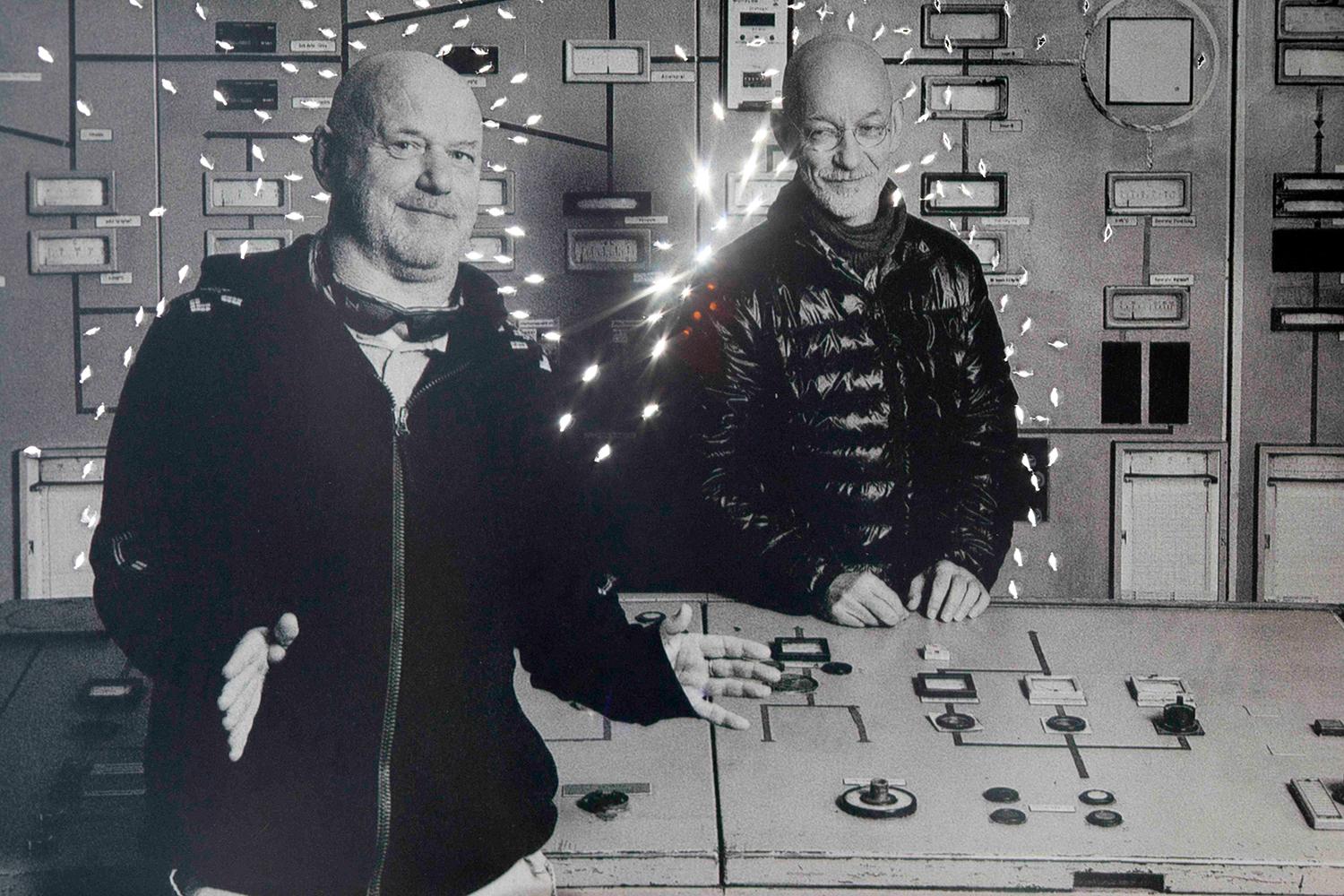

Swiss-born soundscape master Fehlmann relishes the chemistry he and London-native turntable mixologist Paterson have onstage. “We’re aiming to be as fresh and intuitive as we can get each evening,” Fehlmann says. “We have quite a bit of a routine together. We stand fairly close together onstage, so we read our body language to see where the other guy is going to — whether it’s the moment to take something out, or leave it in. That nice level of the personal social exchange of creativity makes it really worthwhile for us.”

The Orb shook ambient house off its foundations with 1991’s mind’s-eye-expanding The Orb’s Adventures Beyond the Underworld and 1992’s trip-hop chillfest U.F.Orb. The latter included an edited-down version of their 40-minute sample-tastic excursion into the Blue Room. In 2012, their reggae-tinged collaboration with Lee “Scratch” Perry saw a riddim-infused update of 1990’s look-to-the-sky narrative Little Fluffy Clouds that Perry redubbed as Golden Clouds. Fehlmann feels Moonbuilding 2703 AD takes The Orb to even newer stratospheric heights, and he spoke to Digital Trends from his home base in Berlin about the new definition of progressive ambient music, how hard it is to capture ideas in real time on vintage synths, and why it’s better to listen digitally when you’re on the go.

Digital Trends: I really like how you play with melody, song structure, and time signatures on the new album.

Thomas Fehlmann: I will take that as a compliment! We developed very early on our own way of “Orbing” things. (chuckles) We’ve kept developing it over the years, and I’m happy to present where we are on Moonbuilding, because I do feel we’ve reached a new level with it.

Is it fair to call this a “progressive” album?

Very much so, yeah! In a way, when Pink Floyd released their recent album [2014’s The Endless River], Nick Mason [Floyd drummer] stepped up and said, “We’re actually sounding like The Orb now.” Now I can say that this Orb album is the one that sounds the most like Pink Floyd! (chuckles)

“We really lock ourselves away from the outside world to just focus on the work.”

Did you grow up with Pink Floyd in your record collection?

Oh yeah, my first album going into the Pink Floyd world was Atom Heart Mother (1970). That’s the one with the cow on the cover. I loved that! They came to Zurich [on December 12, 1972] to play Meddle live, with Echoes and all that stuff. I was about 14 when I saw them. I didn’t want to miss that opportunity.

That must have been one amazing show. I feel like there’s a nod to the epic head trip of Echoes about 15 minutes into the Moonbuilding album, with that series of pings we hear in Moon Scapes 2703 BC.

OK, well, there you go! There is also a bit of a thread with our friend Youth, who did some production on [The Endless River]. It was an honor to hear Pink Floyd use The Orb as a reference on that album in one form or another.

What gear are you currently using?

The basis of where it all comes together is Ableton Live. The reason for that is it enables us to work at a speed that doesn’t hold us back. I remember the times when we worked with 24-track recorders and arcane samplers, where it took ages to get things in time and in tune. These days, as soon as we feel technology is slowing us down, we abandon the idea and go for something that is more immediate, because we very strongly believe the music is in the head, rather than in the machine.

I remember back to the time when we waited for the release of a new synthesizer from this company or that company. These days, we have a bunch of old, trusted machines that we go back to pretty much all time, and don’t incorporate so much new technology anymore. It’s just a waste of time getting to know those machines. That’s an idea that’s dried out for us, to be honest with you.

Do you have a favorite synth from back in the day that you’re still using today?

Oh yeah, I can talk loads about that! (chuckles) I went back to my very first synthesizer from the late-’70s. It was not chosen so much for its audio facilities; it was chosen more for its affordability — and that was the Korg MS-20, a pretty rough machine. I have more than one of them these days — and I’m sure glad I do! I also have some Oberheim machines, the OB-8 [analog synthesizer], and I have a programmer for my Matrix 1000, which allows me to be quite flexible.

On the digital level, I have some Nord Lead A1 machines, which I really like. I have them rack-mounted, so they don’t take up too much space. Those we go back to on a very regular basis. My Fender Rhodes also gets regular use. I hook that up with a Moog Moogerfooger ring modulator and a Roland Space Echo — that’s endless joy for me.

“If technology helps, then we embrace it. But if it gets in the way, we kick it out of the room!”

There are a number of recurring themes throughout the album. Something that shows up on Side 2 recurs on Side 4 — if we’re talking about Moonbuilding in its vinyl form, that is.

We didn’t look at it in terms of how many times something repeated, but in terms of where it fitted. The conceptual thing was not so much to divide it into four sections; we just decided the give each side different moods. Some themes are supporting the down-tempo side, but generally, the overall angle of those two machines I just mentioned — the Moogerfooger and the Space Echo — are on the record all over the place.

I also have to mention that Alex’s most important tools are the Pioneer CD mixer and the DJ mixer, where he uses the effects quite well. They work in tune with the speed of thought when we’re coming up with ideas, you know.

It’s that constant battle of having the thought in your head and trying to get it out through the machine as fast as you can, right? Would you say it was more frustrating back in the days of 24-track because it took too long to realize the ideas you had?

What we discovered was that, in those days, when putting ideas into shape for production, you seemed to forget what was going on around it and the other ideas that were sparked off by it. You’d have one idea going, and the other bits that came to your mind while you were hearing it got lost into the mangle of technology.

In a way, it was almost like having too many ideas for your own good, because you couldn’t replicate them all exactly at the time you had them.

Yeah, the cooking just took too long for the ideas to stay in the picture! (laughs) I often feel that Alex was being held back, because he was mainly coming from the corner of the studio where the DJ setup is, and sometimes his ideas didn’t get across to the guys at the desk. He had so much waiting time. Today, I’m the one adapting to the speed of his new ideas. To be honest, I feel our whole work has benefited from that option.

Would you say that, after 20-plus years of collaboration, you guys have a good shorthand for how you work together?

Oh, we’re actually impressed that things are still exciting for us when we go into the studio. We don’t have to kick ourselves to get going and say, “OK, we have to go to work.” The fact is, Alex lives in London and I live in Berlin. But most of the time, Alex comes over to Berlin to record, and then we really lock ourselves away from the outside world to just focus on the work. We treat it as, you know, “OK, this week is production time,” and we’re not distracted by our day-to-day lives. That’s something we learned was the most fruitful process for us.

What’s your preferred listening format for the Moonbuilding album?

“If technology helps, then we embrace it. But if it gets in the way, we kick it out of the room!”

The most perfect way would be the vinyl. For me, listening to it on digital players, with iTunes and at the MP3 level, would only be for listening on the road. When we’re on the tour bus, we have the rumbling from the motor and people talking, so the music serves a more atmospheric kind of duty. That’s when music becomes more of a social element, right? You really have to sit in front of a pair of speakers to digest it in its original form.

About 10 or 12 years ago, there was a new love affair with the lo-fi — not sounding crude as much as how you treated your machine, and the whole lo-fi aesthetic freed us up a bit to think more about the content than the sound quality. Of course, I take care of the sound quality because I take care of that board, but I take it along the lines of, “Be quick, be effective with the ideas, and don’t get wrapped up so much by the technology.”

Sometimes ideas get lost in the air if you’re going for precision over content.

Yeah. Forgetting or losing the idea is one thing, but finding out the idea that you’re working on doesn’t have the original spirit of what you thought of in the very first moment — that is a special moment to capture that spirit, and that’s very much what we’re after. This record is the closest to the way we feel about the music that’s inside us.

As a listening experience, you really have to go from beginning to end in the order you present Moonbuilding to us, because it’s a complete story.

Yeah yeah yeah! It’s, as you say, a whole story that we’re telling on this one — a poetic story. And you have to listen and focus on the lines in between as well.

It’s also a repeat-listen kind of record where all the textures on Lunar Cave were better revealed to me after the third or fourth listen. Same thing with the bass sweeps in Moonbuilding. I got more out of it each time.

Yeah, man, I’m glad you hear it that way too!

What kind of turntables are you guys using?

We’re very practical, being DJs, so we have Technics. We didn’t compare those with more high-end machines, because some of the venues we play have pretty crude sound systems. So I make my adjustments for those rooms rather than create a surround-sound mix at some fantasy level at home that I’d never be able to recreate on the road.

You grew up in Switzerland, and then moved to West Germany. What was the first record that had impact on you as a listener?

That’s a good question, because I still have a very good relationship with my first Beatles record. I was about 7 years old, and I had a Beatles record on my wish list. My aunt was very smart to give me one, and I have been addicted ever since. The first album I had was Help! (1965). But I had to take the record player into the cellar in order not to annoy my parents. They were definitely not behind that music at the moment. But to be downstairs, on my own, without any restrictions, maybe allowed me to be more dedicated to it as well. For me, there was nothing too sad about going into the cellar, because that was my favorite spot. And collecting records, 7-inches, was my favorite pastime. Often you could tell what track was next just by the surface noise you’d hear before the song started.

I have a few records like that too. When did you know you wanted to make music yourself?

Growing up in the countryside in Switzerland, the dreaming of it was always allowed, but to be in the frame of mind that I wanted to make a profession out of this was just out of the question.

When I moved out of Switzerland and over to Germany, the first thing I studied was fine art, but I discovered the way of communicating with music was more of what I was after than communicating with art. I felt the situation where if you would hang some art in a museum, you wouldn’t even meet the people who would look at your pieces. What’s that all about, you know? (chuckles)

“We very strongly believe the music is in the head, rather than in the machine.”

We mentioned Pink Floyd earlier. I thought Metallic Spheres, the 2010 record The Orb did with Floyd guitarist and vocalist David Gilmour, would be a great one to hear in surround sound.

Ahhh. Orb music, with its big ambient content, should be great for adding additional atmospherics to surround you, but then you’d have to have the guitars playing there onstage with you.

You can just have David plug in from the Astoria [his houseboat recording studio] on the Thames, and play right along with you that way.

That would be fantastic! But since you mentioned David playing from the Thames, one thing that’s important to us is that we’re always together in the room when we work. We never exchange files or anything, because the quality is a different one. My ideas, and my adaption of Alex’s ideas in the same room — we don’t have to analyze it that much. We just accept it. After all, creativity and the social element that we’re after — it just happens differently when there are two people in the room, rather than hacking stuff up and exchanging it via file. We try to avoid the clinical approach. Our main goal is to make music, you know. We have to take the factors into account that help make good music. If technology helps, then we embrace it. But if it gets in the way, we kick it out of the room!

Are you still excited to get onstage?

Totally. We like to improvise when we play, and I have the role of bringing in the tracks we’ve produced. Alex is the free soul who improvises with sound effects and different beats. He exchanges them every night. Sometimes they’re unusual and puzzling, and I have to adapt to what he’s doing. That keeps it fresh and new, so that no show sounds the same as another one. Sometimes I go places with my pre-produced Ableton Live material — places I thought I’d never be able to go. But Alex is very quick in picking up the spirit in the room and knows when to wake people up or bring people down — whatever’s appropriate for the moment.