“If I make a piece of music, I want to hear it as clearly as possible.”

Electronica pioneer Tom Jenkinson — better known by his nom de mix, Squarepusher — has declared himself a free man. After years of toil and experimentation, he finally put the finishing touches on a custom programming system he’s been working on since at least 2002, one he’s dubbed “System 4” — the reasoning being, “in very poor terms, it’s the fourth significant development of it.” Nonetheless, Squarepusher feels utilizing his own software while creating new music is quite liberating. “It puts me out of the reach of tech companies and out of the reach of gear manufacturers,” he explains. “And I can determine my creative path, because I’m not being set into a predetermined creative structure that’s governed by engineers, not musicians.”

The first fruit of programming labor can be found on his latest album, Damogen Furies, out today on various formats from Warp Records. Furies percolates with the furious breakbeats and acid-house constructions the man is known for, from the blisteringly sizzling Rayc Fire 2 to the cutting percussive rage of Exjag Nives to the rat-a-tat skittery doom of Baltang Arg. “If I have one thing as a legacy, it’s trying to keep people awake to the concept of the future,” he says. “I want to pass that baton on that’s been passed down from Zappa, Beefheart, Miles Davis, Messiaen, Stravinsky, and Schoenberg. I’m not trying to put myself in the same league as those guys,” he continues with a chuckle, “but the one thing I do know is I’ve taken something from them, and I do feel obliged to pass it on. This is one of the reasons I work alone. I wouldn’t want to put anyone under the pressure I put myself under.”

Digital Trends rang Jenkinson across the Pond before he embarked on an international tour to discuss the advantages of using one’s own software, why composition may be more important than resolution, and why he feels he’s still a punk. Do you know Squarepusher? He’s more than just a Hard Normal Daddy.

Digital Trends: What was the main goal for developing your custom programming software?

Squarepusher: The main point of it was to make available musical possibilities that I didn’t see being available through off-the-shelf software or conventional musical hardware. And one of the advantages of it is portability, because it runs inside a computer. It’s a little bit more streamlined, shall we say. All of the intricate stuff is happening inside the computer.

Were you excited to record an album using only your software?

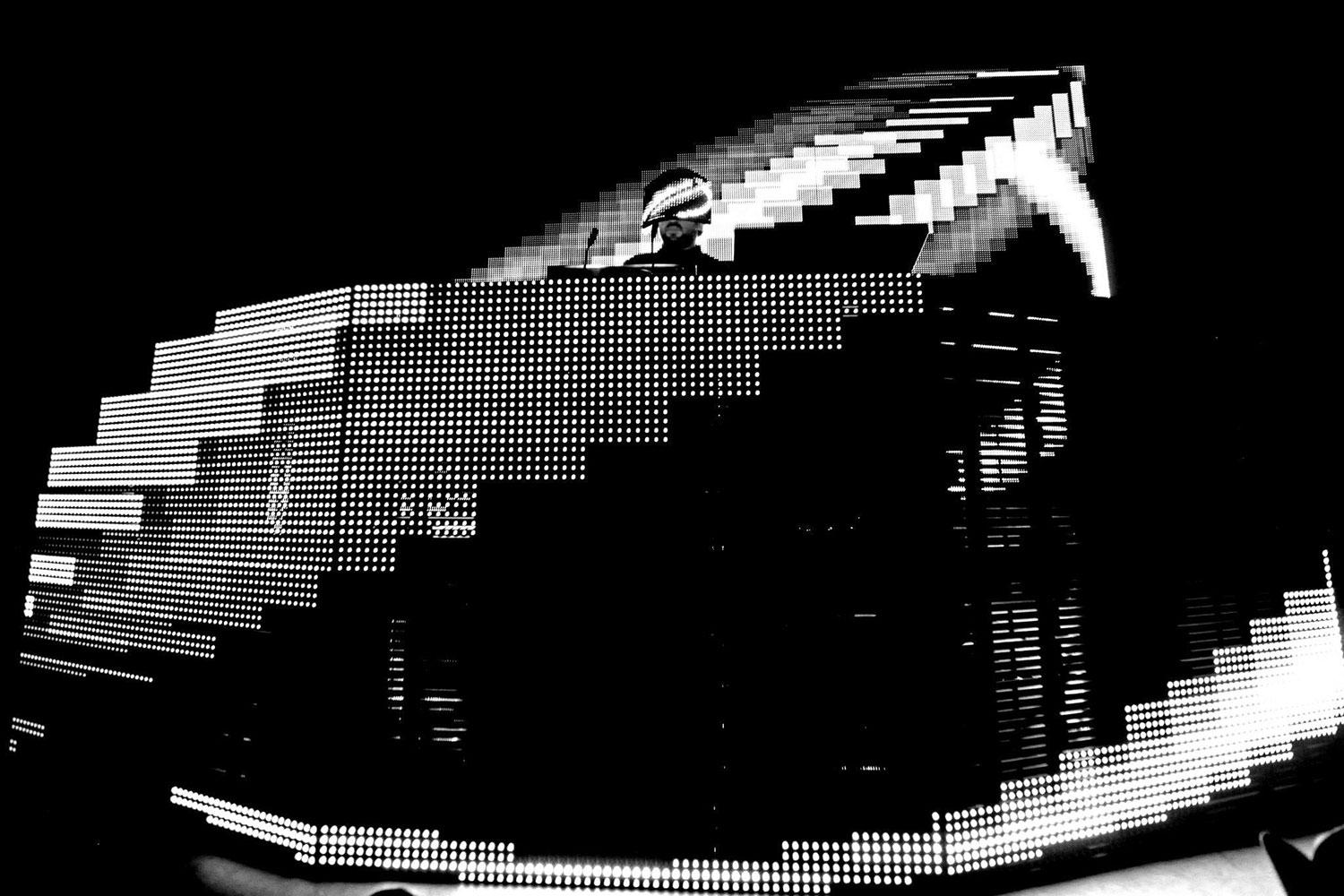

My initial idea, when I started writing this material, was to write music I thought would be interesting and enjoyable in the live context, both in terms of me performing it but also in the perspective of the audience. That’s how it started. It didn’t start out as an album project. With that in mind, it had to be musically interesting enough to do a show and inherently oriented toward live performance — and therefore, the setup on which it has to be done has to be portable.

The idea was that it would be the same in the recording studio as it would be on the stage. What I’ve typically had to do in the past was make adaptations, cut corners, change things, and essentially lose degrees of freedom when I end up taking it to the stage. Some of my albums were never really designed to be played live, but the album before this one, Ufabulum (2012), was the sort of album I envisioned not only in the live context, but also in the home-listening context.

“MP3 — fuck that.”

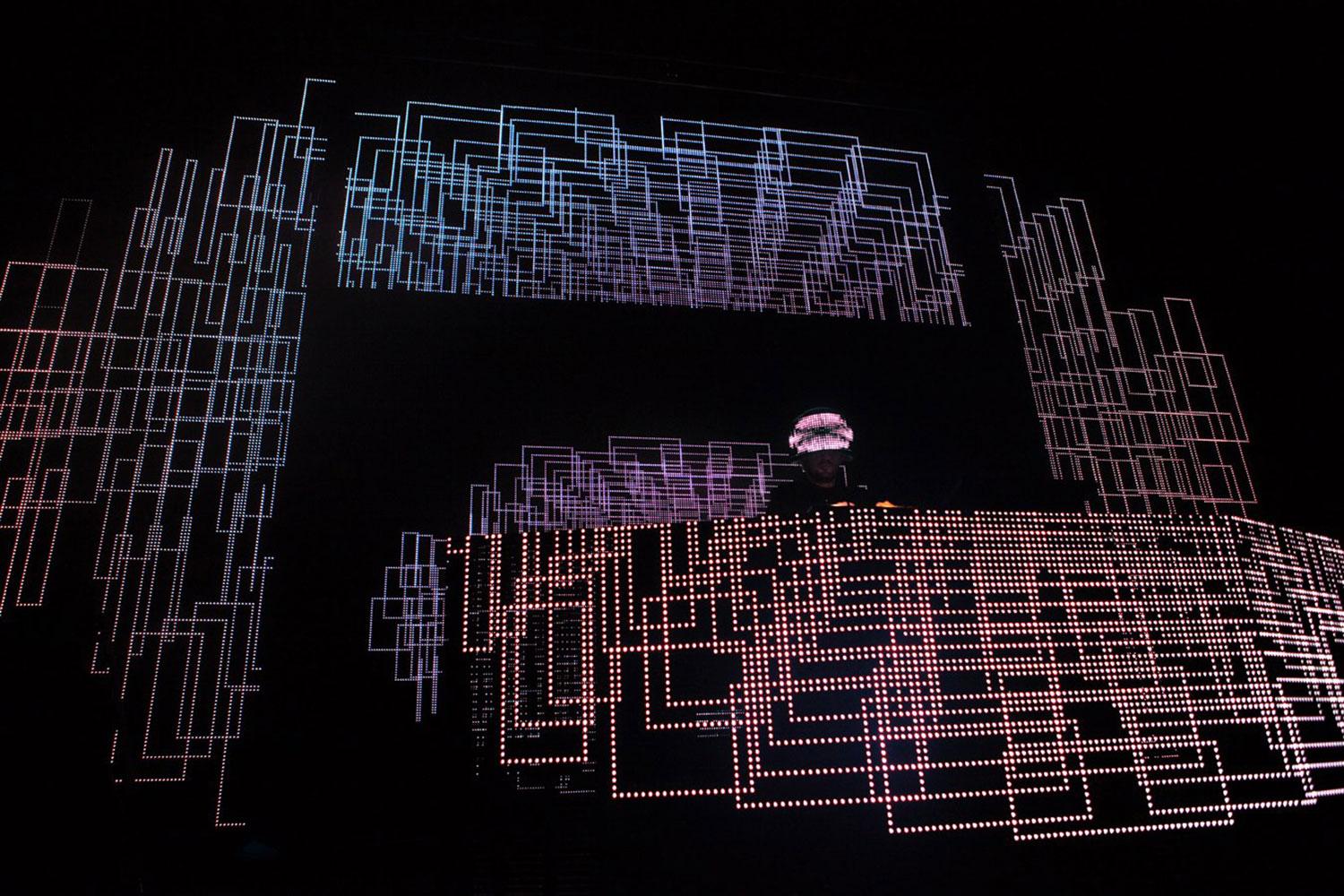

In order to take it to the stage, I had to make significant adaptations to the setup, because it was done originally using big hardware. The big mixing console was very much a part of the sound of it. And the Yamaha CS80 synth — I don’t know how much it weighs, but it’s not the sort of thing that’s practical to take around with the other racks. It’s all a bit 1970s, and you look at the freight bill and think, “Hang on a minute, how did I end up taking two-thirds of a ton of equipment with me as I go?” [The Yamaha CS80 polyphonic analog synthesizer, first released in 1976, weighs over 200 pounds.]

Taking all of that gear on the road kind of turned you into Rick Wakeman.

(laughs heartily) Yeah, I left the gown and the headband at home. (chuckles)

The big console you mentioned — is that the Euphonix mixing desk?

The console on Ufabulum? Yeah, yeah, that was the Euphonix CS3000. I’d actually used that on a couple of records before that too. Damogen Furies was recorded through the CS3000, but the mixdown process — the complex stuff with all the automation, the shaping of the sound — was all happening inside the box. It was just splitting channels out through the Euphonix, with a little touch of EQ here and there, and that was it. The CS3000 was not really so much of a big feature on this record. In terms of what we do onstage, the Euphonix was being used to sum all of the signals in the studio, and onstage, that summing process is happening inside the computer instead.

What other gear did you use on Damogen Furies?

All of the basic process of generating the source sounds, shaping them, processing them — all of that was happening in my own software setup. The additional bits of hardware were as minimal as I could make it. For sequencing, I was using an old Yamaha QY 700 hardware sequencer, but that comes with me on the road, and I’m using that one onstage. Other than that, it was a MIDI interface, an RME MADIFace XT audio interface, and then, to do the mixdown, I was using the RME, and just split the channels up and put them out for analog outputs. And that was it, really.

Do you feel the mixing process for this record was easier than some of the previous ones?

Not really, just that all of the hard work was done in automation inside the computer. None of the hard work was done on the console itself. The console, as I say, was just acting as a summing box. Once it came to the actual process of compiling the record, I went back through and just fine-tuned the mixes. A lot of the automation and the mixing process was done contemporaneously with the composition. It’s not uncommon for me to do that.

I tend to get a rough sound picture in focus while I’m writing. It feels more awkward to write if your sound is all out of balance. I find it harder to get clarity when it comes to contrast and mixtures of instruments, so the majority of the mixing was done during the composition process, and was fine-tuned right at the end.

What are your thoughts on high-resolution audio? Are you recording at 96/24, or 88/24, or…?

I’m not obsessed with these kinds of details. People spend a lot of time trying to get the highest degree of recording quality for their work, but my theory is very much along the lines of the cliché that the heart of a good drum sound is a good drummer. The key thing about all of this is that the compositions are sufficiently strong. What survives is good writing, and that’s the end of it. It doesn’t matter how well or how badly recorded it is — as long as you can hear what’s happening in that recording.

“You can hear a piece of Bach on a phone, through the most low-quality reproduction available, and immediately your ear locks into it.”

There are certain pieces of music that haven’t been well recorded, and it doesn’t mean I can’t enjoy them. Although a good recording might let you hear it a little more clearly, as long as you can get the general picture of it with the sound, then I’m not too worried. I’m not going to deliberately record it badly, but I’m not going to spend hours and days and weeks obsessing over that side of it. I have a standard I think works for the material, and then leave it.

Because I was using this very, very CPU-intensive DSP process on this record, I had to keep the sample rate to 44.1 to stop the CPU load to escalating to the point where it was starting to make the audio drop out, with clicks and silences in there. So, in the end, I went with 44.1/24. In any case, that’s the resolution of what I’m putting out with the soundcard — and there’s no need to stretch it beyond that, because it’s entertaining other kinds of problems with the audio, even if it’s achieving a greater degree of resolution.

So it’s analog out through that and into the CS3000, and then recapturing at 44.1/24. I could capture it at 96, I guess — but those details don’t keep me awake at night. What does keep me up is thinking, “Have I got all those notes in the right place? Is that chord progression going where I want it to go? Does that chord sound off in there, does that chord sound interesting, does it sound like I couldn’t be bothered?” Those are the kind of things that keep me awake at night, thinking, “Have I done my best?” I don’t sit there thinking about sample rate and bit depth. That’s someone else’s problem. (chuckles)

I do agree that if there’s not a memorable hook or melody, like we have on Furies songs like Stor Eiglass, then high-res can’t just make it “better.”

I think it’s really interesting where you can hear a piece of Bach on a phone, through the most low-quality reproduction available, and immediately your ear locks into it and you start keying into it, paying attention, and enjoying the flow of the melody and the counterpoint. It’s all there — even through the most objectionable form or reproduction, it’s still there, and that fascinates me. You’re thinking, “OK, I spent this much on a pair of speakers and an amplifier,” and yet, just literally hearing this thing through a mobile-phone speaker has sent a shiver up my spine, you know? It shows you that, OK, reproduction is an important detail, but in the center of it all is good writing. That’s how it works for me.

The thing that makes music last is the writing, the harmony, the melody, the interest of the interplay of the musical elements. From there, if it’s a great recording — brilliant. That’s a bonus, but it’s not the essential condition.

That’s a fascinating point, because I’m a high-resolution guy, and I like hearing music in the best way possible. I always feel like I might miss something in an MP3, especially considering the detail inherent in your own work.

Oh yeah, look, sure, MP3 — fuck that. I can’t listen to MP3s, because I hear all these strange atonal artifacts. No, I can’t deal with MP3 at all. PCM is fine. Look, there’s no excuse for MP3 anymore. We’ve all got way enough bandwidth. It’s just ridiculous. Everyone’s got enough bandwidth now for PCM to be the prime music distribution. All of that streaming compression — I don’t support any of that, that’s bullshit.

But it’s a really tough balance, because it depends somewhat on the music on how much to concentrate on the quality of reproduction. I’m doing lots of different DSP processes, which in themselves bring out and emphasize the strange atonal overtones in the pitches. It’s different, really, for a piece that is much more straightforward, one based on a melodic line. If there’s a very tonal basis for the piece, then a little bit of a compression artifact here and there isn’t going to make a massive amount of difference.

“I’m quite used to trying to perceive the detail in a mish-mash of hiss, in poor sound quality.”

Now, taking that mobile phone example further — I can see Bach surviving that, but I can’t see Wagner. Bach is not really particularly dependent on dynamics. There are certain things that are dependent on the relationship between pitches, but that information can come through on low-quality reproductions. But where it’s all about textures and timbre, the subtle nuance in the way that things are played, and the tone and sound of the voice, then I think you’ve got a problem with low-quality reproduction. If it’s something that is about counterpoint and melody and those simple tones speaking through the interplay of pitch, then you can get away with low-quality reproduction. It doesn’t really take away from it.

When I started listening to music, I was listening to AM radio and then I was recording on cassette tapes, and obviously the fidelity available on a quality cassette was never that good. In some ways, I’m quite used to trying to perceive the detail in a mish-mash of hiss, in poor sound quality. But for me, I still have to look forward, and I do see high resolution ultimately as icing on the cake. The icing is the music, and the cake is a good composition, you know?

I do know, and now my ears are hungry. (both laugh) We were talking about albums earlier. These days, the concept of putting out full albums has lost its luster in some circles.

Like I said, I started out making a load of stuff to go and play live. I didn’t think about making an album. The album idea came from other people when I played it for friends I work with or people from the label, and so forth. “You’ve got to release this, you really have to. It’ll be a really great record.” I admit, I hadn’t thought about that. The novelty of the concept of releasing a record is, sadly, long gone for me. I’m more into making the music. In itself, the concept of releasing an album doesn’t have any thrill to it. If I feel the music merits it, then I will do it. I make loads of music I don’t release. If I’ve done something that feels sufficiently operative and original and it doesn’t sound like anything else out there in the world, then I’ll put it out. That’s the grounds for me making a record.

Look, we’re in a time where the concept of the album is disintegrating somewhat. The listener, through the ways that they access music these days, is very much more empowered. They can construct their own album, if they like. It’s now possible to cherry-pick the album, or other artists’ albums, and make your own album. And there it is — people go for what they want to hear.

My idea of the album is more along the lines of how it was perceived in the ’60s and ’70s — where it was about a statement, and everything on that album contributed to that statement. It worked as a whole, and you put those pieces together in an order, because they have a resonance with each other, and each to the next, because there’s a meaningful progression between them.

That, for me, principally governs the concept for the way I put an album together. I’m not blind to the fact people are looking at albums in different ways. I’m not making a value judgment on that. It’s just a different way of looking at music.

Is there an album you’d consider to be the perfect “statement,” as you put it?

The one problem I would flag up with regards to the cherry-picking attitude toward albums is, can you imagine coming to an album like [Captain Beefheart & His Magic Band’s] Trout Mask Replica (1969) as a new listener? You don’t know Beefheart’s work, and you don’t know what to expect, as it were. The first thing that will probably hit you is a sense of being baffled by what’s happening, which is a quite unprecedented experience.

“The novelty of the concept of releasing a record is, sadly, long gone for me.”

That album is tough listening, especially if you don’t know what you’re in for.

It’s tough listening, exactly. And I think if you approach it with, shall we say, a purely hedonistic attitude — “I want my desire satisfied, I want to hear stuff that’s cool, I want to hear stuff that I can latch into straightaway” — that album is going to fox you. If you take that attitude with it, you’re never going to get anywhere. You’ll discard it and go, “Well, that’s nonsense. It’s just like a lot of noise.”

I find the hedonistic, basically cherry-picking attitudes towards records will disallow those kind of experiences. Anyone who knows Trout Mask Replica has had to persevere with it. If you persevere with it, you get somewhere. It’s gradually revealed through progressive listenings. I must have heard that record, I don’t know, 150 times, and I still feel I’m learning more about it now. And that for me is a wonderful thing. It feels like it’s continually evolving. It’s a live thing that continues to live in a musical world, and I find that to be the highest description I could give a piece of music — it continues to develop, it continues to show me things, and it continues to surprise me. I find it absolutely fascinating.

I think “persevere” is a great word when it comes to Trout Mask Replica. I know it’s taken me years to get deeper into it. It’s not so much peeling an onion as it is unfolding an artichoke, because the more you get inside it, you find layers and things you never knew existed. That’s the only way to get into that record, and I felt I owed it to myself to keep with it. It’s got to marinate.

Yeah, yeah! That’s right. Absolutely. There’s something about it that pulls you through that’s really challenging. And like I say, that’s the highest recommendation I can give to something is that it continues to live. And I admit, if there’s something I’m trying to do with music, it’s to make things stay alive in people’s imaginations. They don’t just go out there and get nailed down as this particular statement in this particular era. I very much hope the things that I do can have something to say in every subsequent era. They will continue to live, and new listeners will continue to shine light upon it.

Finally, as someone who’s considered a pioneer in the electronica and drum-and-bass universe, how do you view the state of EDM today?

It seems like music that was maybe designed for people with really short attention spans. I’m not looking at this stuff every day, but it kind of sounds like music used to advertise trainers. In some ways, EDM sounds to me like a very professional sort of music, and I feel uncomfortable with any sort of professionalism in music. Its focus is beyond things germane to music.

It’s sort of like when punk went mainstream, which seemed to be the exact opposite of what that whole scene was about.

That’s a very good point! People who now want to create a moment of punk will use the gestures embodied in the Sex Pistols, the records of The Clash, or whatever. The important thing — and this is why I’d say I’m more of a punk than they are — is to take to the mentality. There are hallmarks of philosophy in my music that people would say, “That’s not punk!” Punk was a reaction to that sort of thing. No, look a bit deeper. You’ll find the mentality of punk is not applied to one specific set of musical aesthetic. It adapts and changes according to the times.