He may be skeptical, but he is also hopeful. McGregor is the CEO of Truepic, an image authentication company that’s taking a high-tech approach to fighting fraud and fake news. He describes the service as a sort of digital notary for images. It automatically verifies a photo at the point of capture, proving its realness to anyone who views it, be that a claims adjuster, apartment hunter, or someone looking for a date.

Truepic is a digital notary for images that adds layers of verification for authenticity.

Truepic works through a mobile app — either the company’s own or within one of its client’s apps that incorporates the Truepic SDK — but the real magic happens in the cloud. As McGregor described it, Truepic is essentially running a server side software camera; the camera on your phone is just a “lens.” The server performs a wealth of data analysis on the images it receives, then encodes them to the blockchain to provide an extra layer of security against manipulation.

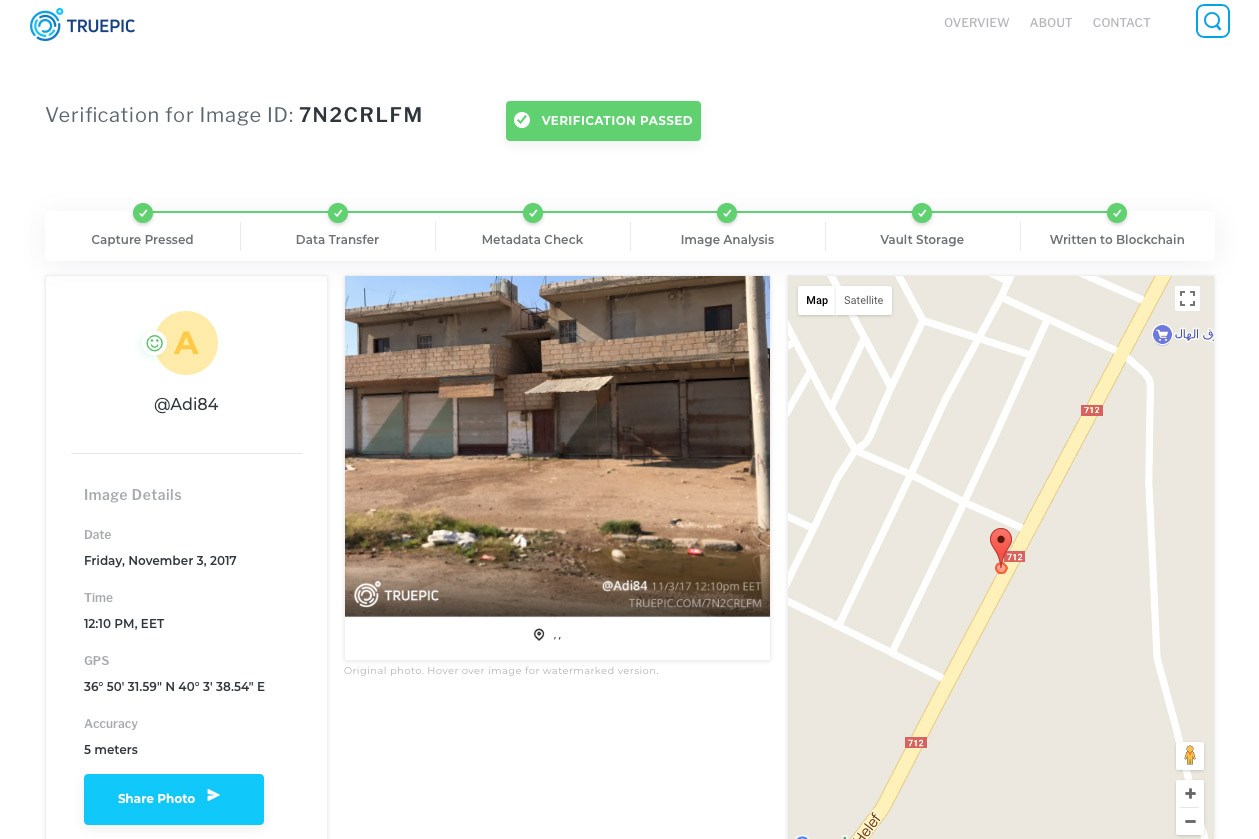

“From the time you press the shutter button, it’s roughly 12 seconds for [the picture] to land on our server, be stamped with server side metadata, complete various computer vision tests, and hash that data and send it to Bitcoin,” McGregor explained. “We are creating an immutable copy of that data that will forever stay true.”

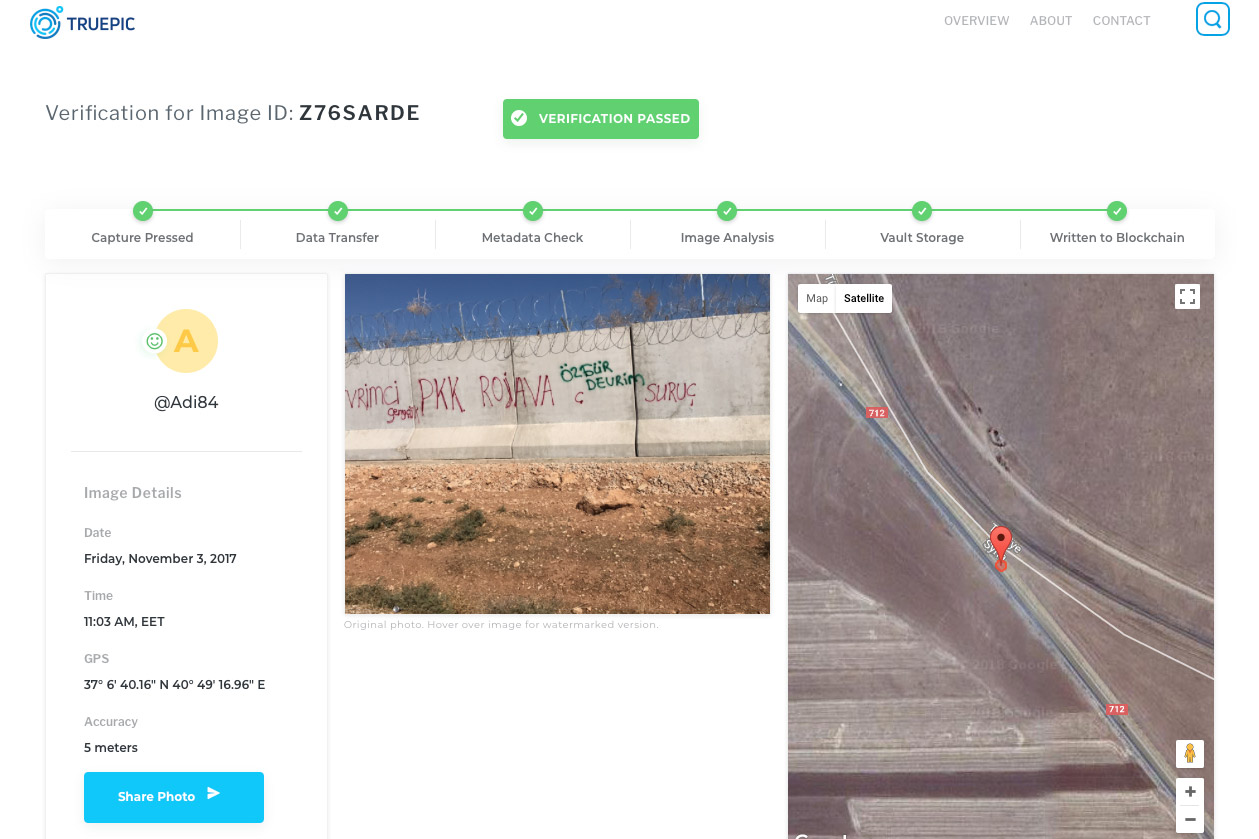

When a user takes a picture, it is watermarked with the Truepic logo and given a unique serial number. Each image has a specific verification URL which can only be accessed with that unique number, giving the recipient a way to double check that it is authentic, and not just edited to look like a Truepic verified image.

The service uses much more than an image’s embedded metadata to prove authenticity, pulling as much information as possible from a phone’s additional sensors. For example, it doesn’t just rely on GPS to determine location; instead, it uses surrounding Wi-Fi signals and even barometric pressure readings to confirm the GPS position. Truepic also time-stamps images on the server side, so even if someone has tampered with their phone’s clock, the image will show the true time it was taken.

Simply being able to trust that a photo was taken where someone says it was can do a lot to combat image fraud. In online dating, for example, this can let you know that the person you’re talking to is actually in your city — and not trying to scam you from halfway around the world. A dating app can integrate Truepic’s SDK and require its members to take a selfie with it to prove their location. (To satisfy privacy concerns, Truepic lets users choose to just show their general area.) A positive side effect is that the time-stamped photo would also prevent people from posing as much younger versions of themselves — a less financially damaging, but perhaps equally annoying type of fraud.

Romance scams don’t yield the same total losses as other types of fraud, but they impact individuals more strongly, making it an important problem to solve. The FBI estimates the average damage is in the range of $10,000 per victim.

“What we saw early on were people taking photos of other photos.”

Verifiable date and location stamping may work to combat romance scams, but it can’t solve everything. Insurance fraud presents a tougher challenge. “What we saw early on were people taking photos of other photos,” McGregor said. A Google image search makes it pretty easy to find a photo of, say, a Honda Civic post fender bender, and simply snapping a pic of that photo with your phone is enough to create a “new” image with original metadata. Now you can send off your Inception photo to the insurance company and kick back while you wait for the check.

Well, maybe you could have done that — except that Truepic knows if you’re just taking a picture of another picture. While the company is tight-lipped about the specifics of its image recognition technology, McGregor offered a few details about what’s going on under the hood. “We’ve built a number of tests that allow us to understand if the image being captured is of a 2D surface or an actual 3D environment,” he said. “We are able to identify that with a high degree of accuracy.”

The FBI attests that combined insurance fraud (not counting health insurance) totals $40 billion per year. But being able to trust that an image is real isn’t just a way for insurance companies to save money by weeding out fraudulent claims — it can also speed up the review process, meaning legitimate claims get paid faster. Long term, premiums should go down, as well, so everyone wins — well, everyone except the fraudsters.

Empowering citizen journalists

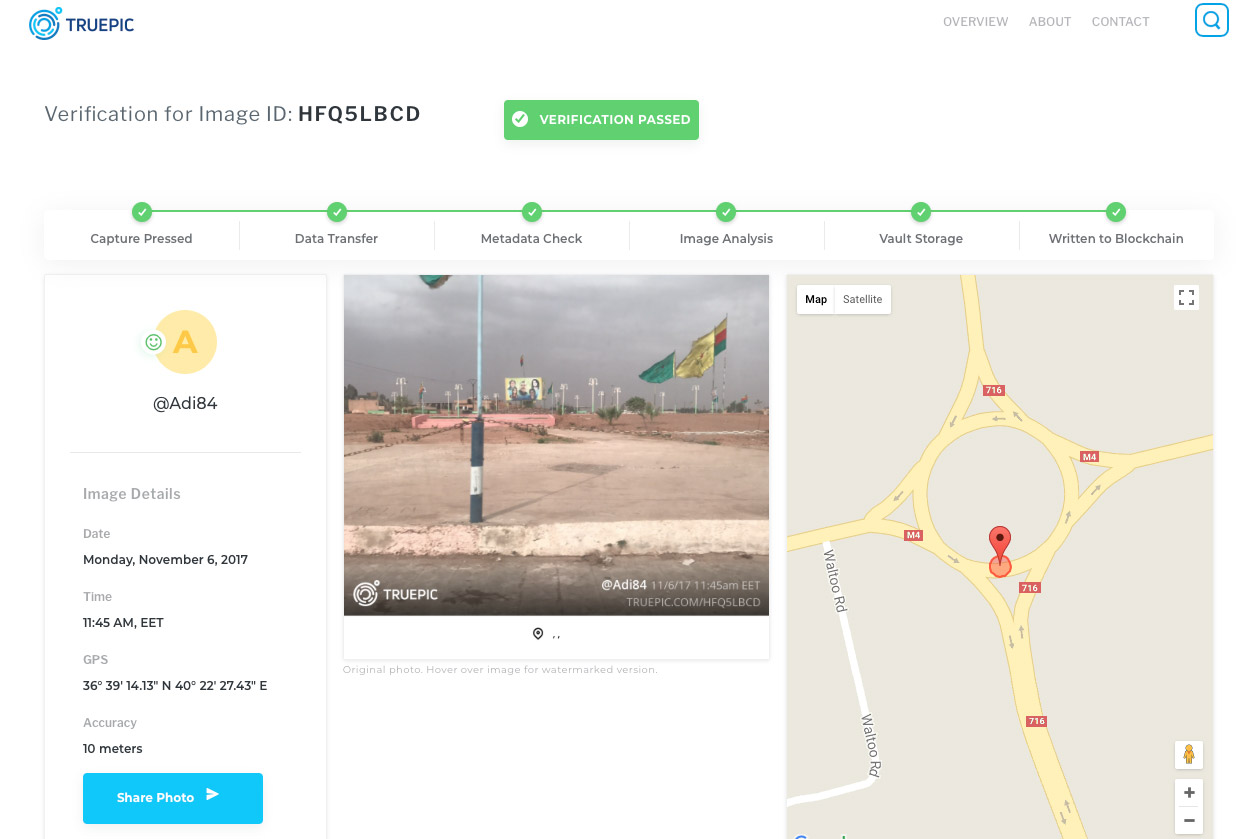

Getting its SDK embedded into the apps of major insurance companies is clearly important to Truepic’s bottom line, but there’s a potentially even more critical mission beneath the service. Mounir Ibrahim, Truepic’s VP of strategic initiatives, joined the company after realizing the potential it had to empower citizen journalists, particularly people living in conflict zones.

Before Truepic, Ibrahim was previously with the U.S. Department of State, where he served as a diplomat to Syria. He spent a lot of time observing protests in the lead up to the civil war that broke out in 2011. “What I saw throughout my time as a U.S. diplomat, particularly the last couple of years, was a rise in images and videos of the most outrageous atrocities around the world,” he told Digital Trends. “Almost every citizen is becoming their own citizen journalist.”

However, the images would often do little to generate the support they deserved. “Other members of the United Nations Security Council would undermine these photos on the ground that their authenticity couldn’t be proved,” Ibrahim said. “It was a way to shrug off responsibility.”

Essentially, this is the opposite problem to what happens with photos used in fake news stories: Rather than someone believing a fake photo was real, people were choosing, in the absence of proof, to believe a real photo was fake. The cameraphone may have enabled citizen journalists, but it’s all for naught if their stories fall on deaf ears. Ibrahim believes Truepic can provide a solution to this, and the app is already in the hands of NGOs around the world, with a presence in some 100 countries.

One limitation here is that Truepic requires photos to be taken on a smartphone. For obvious reasons, it can’t be used to verify an image shot on another camera and merely transferred to the phone. This limits its usefulness to professional journalists working with higher end cameras, although they could still use Truepic to at least verify they were where they said they were.

That said, it is not outside the realm of possibility that Truepic could be expanded to support other cameras, such as DSLRs and mirrorless cameras, but this would require bespoke hardware. Photographers would need to connect a device to their cameras that would send unprocessed images straight from the camera to Truepic’s servers at the time of capture. Presumably, such a device would either need to securely integrate with a photographer’s smart phone, or have its own sensors, GPS, and Wi-Fi built-in.

Such a solution doesn’t exist yet, but Truepic is at least asking the question of how it can expand to support professional photographers. “The roadmap goes in two directions,” McGregor said. “Across different industries, and across different sensors we can integrate with.”

For now, Truepic is providing a glimpse at a more trustworthy future for the internet, one in which we can all be less skeptical about the images we come across.